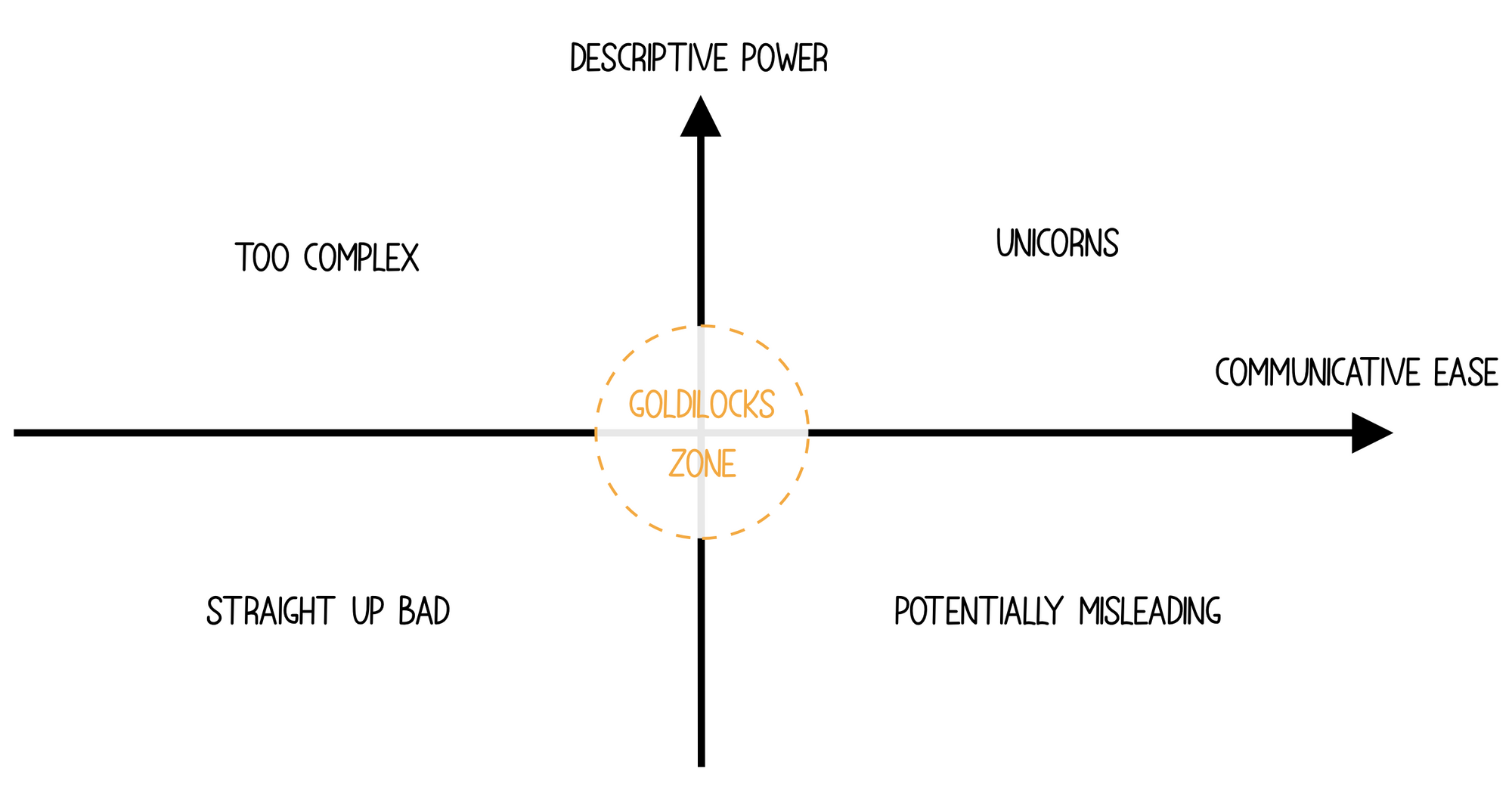

Descriptive power versus communicative ease

Whether in our professional or personal lives, conveying ideas is something we do every day.

As such, it seems almost too obvious a subject to break down into a framework - but I've made mistakes here in the past, and seen others make them too. Here's a stab at a model of a type of pitfall when communicating ideas to others.

A framework

When you are explaining a subject to someone, you are balancing the power of your description with the ease to communicate what you want to explain.

The descriptive power is how far the explanation goes into the detail of the idea you're communicating. A model with low descriptive power doesn't have as much nuance as one with high descriptive power.

The communicative ease describes how well information is passed on. Length is a key factor, but also things like prior knowledge needed and whether specialist terms are used.

The crux of this is: when a model isn't descriptive enough, it has too little power to explain its subject matter - but it is very easy to communicate. When a model is too descriptive, it has lots of power, but it's very hard to communicate.

Here's how I see it in practice:

This might seem a little glib, but I'm not claiming this model is comprehensive - it's just one way of looking at this. In that vein, there are three other key factors at play here:

- What the base complexity of the subject matter is;

- Who the audience is;

- How comprehensive the explanation claims to be.

The goldilocks zone is a moveable feast; submitting a study to an academic journal and giving driving directions are starting from two very different points. And when giving driving directions, if they are prefaced by "I'm not quite sure as I've never been, but I think it's near..." then it's much less of a problem when they have low descriptive power.

I think how comprehensive the explanation claims to be is the key point here. When something claims to be comprehensive, and is very easy to communicate, it's often mislabelled as "common sense".

In this kind of case, it's pretty easy to hide that the model given doesn't have the descriptive power to back up the claims being made. There are plenty of examples from the political world here (see: "our country is in too much debt, so we need to tighten our belts and stop spending").

Getting it wrong

Here is an article titled "Traction vs Growth" that I believe sits in the low descriptive power, high communicative ease space - but that also falls foul of the "comprehensiveness" test (sorry to pick on it, it's just the most recent example I've seen).

Although it opens with "Broadly speaking", it goes on to be pretty proscriptive about the "three phases of growing" that a startup goes through. The first stage it talks about is "Traction", and the article gives a suggested metric to focus on while in this stage:

Plain and simple your eye should be on retention. If your product does not retain users, there is no point in growing the top of the funnel.

Hang on - what if my startup, for instance, sells mattresses? My understanding is that you are supposed to replace a mattress every 6 to 8 years. That's a long time to wait for my customer retention metric to play out.

In fact, I can think of plenty of other examples of business models where the retention metric isn't as important as others in the early stages. But explaining that would make the article much less snappy - and so we are in the muddy waters of the "potentially misleading" part of the diagram above.

Here's another part of the article from the "Transition" phase, regarding the advice to focus on just a single marketing channel:

The fastest way to increase growth rate is to expand on something that is already working (until you’ve saturated the channel) rather than trying new channels that you know nothing about.

My response to that would be: Well, maybe. For some businesses that might be the case, but I think it ignores a lot of the nuances around growth in marketing channels.

In my experience, sometimes a channel looks like it's not working for you - then something in your product and/or marketing changes that unlocks it. On the other hand, sometimes a channel bottoms out much faster than its initial promise would suggest. There's also a pretty big range of what "working" means.

I don't think these are the only assertions in the article that fall at this hurdle. I think the entire framing of startup growth into three phases is an attempt to squash complexity down for communicative ease purposes, and I'm not convinced it's a model that would have had enough power to explain any of the early-stage startups I've worked for especially well.

Layering

My one piece of advice on this subject is that when you are conveying complex information and you want to say something proscriptive, the best way to hit the goldilocks zone is to layer information.

By layering, I mean breaking down your message into chunk-able pieces. Start with the key statement, then move down the chain of propositions that underlie it until you get to the base premises that you believe your audience will understand (can you tell that I studied philosophy?)

Here's an example:

Statement:

For most startups, the number one metric to focus on at the earliest stages is retention.

L2 propositions

1. "Most startups" means startups that have a subscription model of some variety, that relies on collecting recurring revenue from the customer every month (often in a B2B context). Other startup models might vary.

2. By "earliest stages", we mean where a startup has launched to market but is pre product-market-fit.

3. The reason that a focus on retention makes the most sense is that...

The more complex the statement you want to make, the more levels of propositions you need to drop down while still keeping the overall top-level statement clear. For instance, I'd probably want to explain what I meant by "product market fit" to some audiences, but not to others.

This isn't necessarily a good way to actually write an article, paper, or have a conversation about a topic, but it is I feel a relatively neat way to think about whether you have hit the right level of detail while keeping things well-communicated.

Think I've failed to communicate this subject well enough? Feedback welcome to elliot@pkld.io